Scientists examine why nettles taste good to elk in autumn

Adobe Stock

Adobe Stock

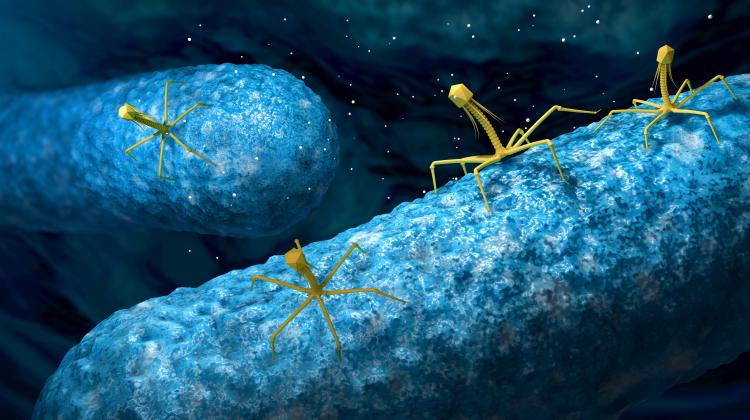

Not only delicious fruits, but also appetizing leaves sometimes 'advertise' certain species of plants to animals so that they carry their seeds. The old hypothesis that 'foliage is the fruit' was first tested by an international team of researchers who examined elk droppings. It turned out that nettle was one of the plants that evolutionarily adapted to be spread by ruminants.

Plants are non-moving organisms. When the environment changes to their disadvantage, they can't just run away. And yet they have the ability to inhabit new areas and respond to climate change. “The seeds allow plants to react in this way,” Professor Bogdan Jaroszewicz from the Białowieża Geobotanical Station of the University of Warsaw told PAP.

There are plant species that invest a lot of resources in producing fleshy, nutritious fruits that are attractive to animals. When an animal eats a fruit, it usually eats the seeds as well. And if those are able to survive in the digestive system of animals, they are carried over long distances.

Professor Jaroszewicz said: “However, there are many plant species whose fruits are not attractive to animals at all, e.g. pods, follicles, siliques, mostly dry and small. And yet animals swallow them and carry their seeds over long distances.”

In the 1980s, the American researcher Daniel Janzen formulated the 'foliage is the fruit' hypothesis. According to Janzen, in the case of some plants that do not produce attractive fruit, the leaves - in addition to being a power factory for the plant - can also perform another important function: attracting animals.

The problem was that this hypothesis had not been experimentally confirmed. The team led by Professor Jaroszewicz, consisting of researchers from Poland (University of Warsaw, University of Bialystok, Mammal Research Institute PAS) and France (University Grenoble Alpes), decided to check whether there were plants that had evolved to spread their seeds in animal excrement at the expense of whole plant (leaves, shoots) being eaten by an animal. The research results were published in Acta Oecologica.

WHICH PLANTS TEMPT: 'EAT ME!'

There are several conditions that a plant must meet to be considered in these studies. The leaves of these plants should be attractive as food, the seeds should be small, relatively spherical, produced in large numbers - and they should be able to survive the journey through the digestive system (and ruminants are difficult - they have four-chambered stomachs!).

The research team assumed that if a plant evolved to be spread (at the cost of being eaten), then the more of its leaves an animal eats, the more of its seeds should end up in the droppings. There is no benefit in an animal eating the leaves if it does not eat the seeds.

In addition, the annual peak consumption of the leaves of this plant by animals should coincide with the peak of the number of seeds in the faeces. The plant should therefore adapt to increasing the attractiveness of its leaves when it produces seeds.

WHAT ELK EAT

To check if at least some plants actually used such strategies, the researchers examined samples of more than 600 elk faeces (collected at different times of the year). Small samples were first taken to test for the presence of plant DNA (environmental metabarcoding). Faeces can be subjected to detailed research and DNA present in undigested remains of plants eaten by an animal can be identified. Thanks to this, scientists learn, among other things, which plants and in what proportions are included in the diet of a given animal. The rest of the droppings - after mixing with sterile soil - were placed in a greenhouse to see which plant species would grow from the seeds present in the droppings. Finally, the results obtained by both methods were compared.

During their research, scientists found the presence of more than 180 species of plants in elk droppings. More than 130 species sprouted from seeds found in faeces, and 150 species were detected by metabarcoding. (Surprisingly, few of these species - less than 20 percent - were detected by both methods, which shows that neither method alone provides complete information about the animal's diet).

Of the seven plant species that were present - and numerous - in multiple samples (allowing for a reliable statistical testing of the hypothesis), three species can support the 'foliage is the fruit' hypothesis. They are: common nettle, yellow loosestrife and purple loosestrife. The more leaves of these plants the elk ate, the more seedlings would grow from their droppings.

In the case of nettle, the relationship was even stronger. Nettle leaves are available throughout the growing season, from early spring to late autumn. However (judging by the presence of DNA in the faeces), elk were most interested in eating this plant in September and October, when nettles produce seeds. “It probably can increase its nutritional attractiveness in that period. Or rather, reduce its unattractiveness,” Professor Jaroszewicz joked. He added that although nettles can deter animals with stinging leaves, they have high nutritional properties (there is a reason why they are used as fodder).

It is still unclear what physiological mechanism causes nettles to taste good to elk in autumn.

Professor Jaroszewicz said however, that elk are not the best species to test the 'foliage is the fruit' hypothesis, because they eat mainly fresh shoots and leaves from trees and shrubs that have different seed dispersal strategies. He said: “In this respect, European bison would be a better subject for research. Bison feed on grasses and other herbaceous plants to a greater extent, and Janzen's hypothesis mainly applies to those.”

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL

Przed dodaniem komentarza prosimy o zapoznanie z Regulaminem forum serwisu Nauka w Polsce.