Toxic Methylmercury May Have Caused Late Devonian Extinction

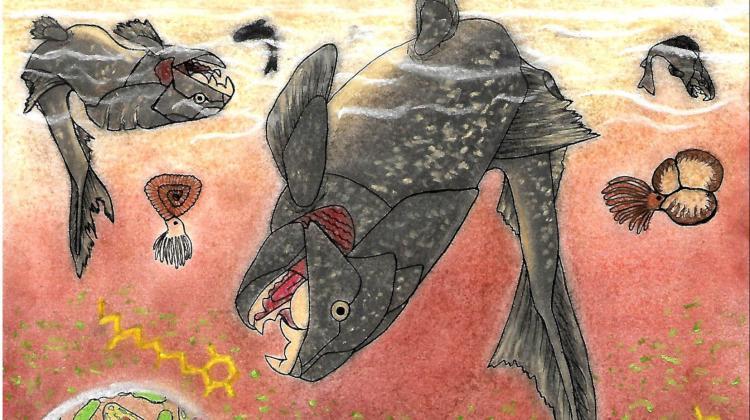

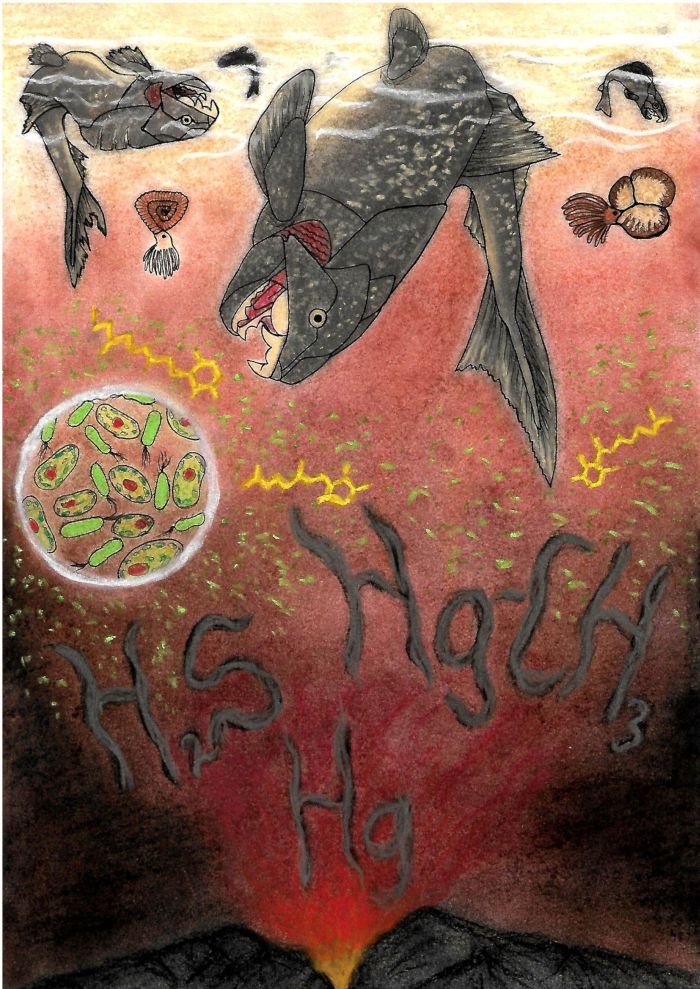

Drawing illustrates an extinction episode during the Hangenberg event about 360 million years ago; credit: Karolina Paszcza.

Drawing illustrates an extinction episode during the Hangenberg event about 360 million years ago; credit: Karolina Paszcza.

Polish scientists have found that toxic methylmercury created by bacteria from mercury of volcanic origin could have caused mass extinction in the late Devonian.

The most dramatic extinction events classified as the so-called Big Five took place in the late Ordovician, late Permian, late Devonian, late Triassic and late Cretaceous.

Geologists from the University of Silesia investigated a slightly lesser known, but also dramatic mass extinction known as the Hangenberg event that occurred in the late Devonian, 360 million years ago (several million years after the Devonian extinction from the Big Five). They showed that one of the reasons for this extinction could be the increase in toxic methylmercury levels in marine and ocean waters.

The late Devonian is considered the golden age of sea creatures: ammonites (cephalopods famous for their spiral shells), conodonts (we know about them mainly due to the remains of their teeth) and armoured fish. These animals survived the Devonian extinction 372 million years ago, but the Hangenberg event a dozen million years later sealed their fate.

Drawing illustrates an extinction episode during the Hangenberg event about 360 million years ago; credit: Karolina Paszcza.

It is estimated that during the Hangenberg crisis, about 50 percent of types of marine organisms became extinct and pelagic organisms (living in the depths of the water) were particularly affected. Armoured fish died out completely, ammonites almost completely, and conodonts were seriously affected.

In addition, anaerobic conditions in marine waters developed globally during this crisis and particularly affected many groups of demersal organisms.

In recent years, increased volcanism has led to mass extinctions. Anomalous concentrations of mercury in the rock layers corresponding to mass extinction intervals would be clear evidence of volcanic activity.

Polish researchers have just confirmed the presence of such high mercury anomalies in rocks from the late Devonian and early Carboniferous in the Carnic Alps (Austria and Italy). This in turn enabled them to reach their conclusions about intense volcanic activity during the Hangenberg event.

But not only volcanoes. The inorganic mercury (Hg) formed as a result of their eruption is considered a highly harmful element. However, between 2 and 38 percent of inorganic mercury is absorbed by the body. Mercury in organic form, called methylmercury, is more toxic and dangerous. This strong neurotoxin is almost completely absorbed by the body and concentrates in organisms occupying the upper levels of the trophic pyramid (they currently include fish, birds and mammals).

Lead author of the study Michał Rakociński from the University of Silesia in Katowice said: “Even small concentrations of methylmercury in seawater can have a deadly impact on organic life. Today it is also a threat to people who eat animals containing elevated concentrations of methylmercury.”

Methylmercury found in late Devonian marine sediments from Austria was formed in the process of methylation of inorganic mercury of volcanic origin - by bacteria. They converted the compound only partially absorbed by animals into a much more deadly compound.

Rakociński said: “Therefore, in addition to the globally prevailing low oxygen levels in water, toxic methylmercury would be another direct factor causing mass extinction at the end of the Devonian.

'Until now, nobody was looking for traces of methylmercury in the fossil record. This is the first study of this type and I hope that it opens new research perspectives for other extinctions.”

In addition to Michał Rakociński, the authors of the article in Scientific Reports are geologists Leszek Marynowski, Agnieszka Pisarzowska and Michał Zatoń from the University of Silesia, and oceanologists Jacek Bełdowski and Grzegorz Siedlewicz from the Institute of Oceanology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Sopot.

The report was co-authored by Italian researchers Maria Cristina Perri and Claudia Spalletta from the University of Bologna and Austrian geologist Hans Peter Schönlaub who specializes in the geology of the Carnic Alps.

PAP - Science in Poland

lt/ agt/ kap/

tr. RL

Przed dodaniem komentarza prosimy o zapoznanie z Regulaminem forum serwisu Nauka w Polsce.